Learn about John Singer Sargents life, work, painting techniques, and styles

Introduction

In an earlier article when discussing the history of painting movements, we briefly touched upon the modern art movements of impressionism and realism. John Singer Sargent was a preeminent artist of the period, widely considered one of the greatest oil portrait painting artists of the modern era. In the current post, will learn more about his life, his oil painting styles, and his portrait painting techniques.

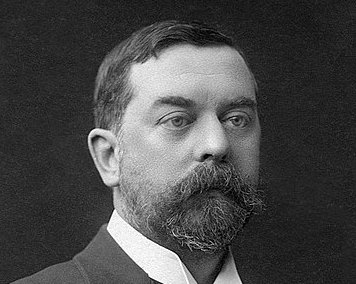

Who was John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent, an American expatriate artist, was the foremost oil portrait painting artist of his period, John Singer was famous for his oil painting portraits of the members of high society in Paris, London, and New York. The colorful impressionist brushstrokes and unconventional compositional approaches he used to capture his sitters' personalities and reputations modernized the long-standing practice of the art of portrait painting. Alongside his friend Claude Monet, Sargent painted impressionistic landscapes while en plein air, expanding his artistic interests beyond portraiture. He also painted formal murals commissioned by government leaders in both the United States and the United Kingdom.

Born to Fitzwilliam and Mary Newbold Singer on January 12th, 1856 in Florence, Italy. John Singer Sargent showed early promise as an artist and quickly began professional painting instruction encouraged by his mother, an accomplished amateur artist herself, and his father, a professional medical illustrator. In his late teens, he enrolled for the first time in art lessons at the Accademia Delle Belle Arti in Florence. Sargent developed his abilities over 1873–1874 and persuaded his father to support his artistic interests. In the spring of 1874, John Singer Sargent traveled to Paris with his father so that he might continue his studies in the hub of European art. Sargent was admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts, the prestigious art institution in France, in 1874 after passing the demanding exam on his first attempt. He participated in drawing lessons that included perspective and anatomy and won a silver medal. He also dedicated a lot of time to independent research, sketching at galleries, and painting in a studio he shared with James Carroll Beckwith, with whom he became good friends.

What is John Singer Sargent known for?

John Singer Sargent was considered the "leading portrait painter of his generation". The portrait paintings of the wealthy and privileged by portrait painter and artist John Singer Sargent provide an enduring view of Edwardian society at the turn of the century. Unlike any other portrait painting artist of that time, he utilized impressionistic brushstrokes, vivid colors, and textures to capture the personalities of his subjects.

Order Your Portrait Painting from Photo Today

Who influenced John Singer Sargent?

Sargent began to study the art of making an oil portrait painting or portraiture under Charles Auguste Émile Carolus-Duran, a french man, in 1874. Over the next two years, Carolus-Duran had a significant influence on Sargent, his style, and his attitude toward art.

Unlike traditional academic oil portrait painting, in Carolus-Duran's atelier or private studio, he was taught the alla prima method of working directly on the canvas with a loaded brush, a method derived from Diego Velázquez (a Spanish painter in the court of King Phillip IV), rather than relying on precise drawing and underpainting. In this method, tones of paint were placed correctly to create an artistic effect. Sargent excelled at his work and soon became the star oil portrait painting student of Carolus-Duran. Julian Alden Weir, an American impressionist artist, who met Sargent in 1874 said Sargent was "one of the most talented fellows I have ever come across; his drawings are like the old masters, and his color is equally fine."

During this time, through his friendship with Paul César Helleu, Sargent would soon meet the leaders of the art world, Degas, Rodin, Monet, and Whistler.

Handmade Art Reproductions & Landscape Paintings

Did John Singer Sargent marry?

The prolific oil portrait painting artist John Singer Sargent was a bachelor and never married. He had few close relationships outside of the immediate family and social circle he belonged to. He had many friends, including noted author Oscar Wilde, and author Violet Paget. He had intimate relations with British painter and lithographer Albert de Belleroche. "Sargent's portraits of Belleroche, in their sensuality and intensity of emotion, push the boundaries of what was considered appropriate interaction between men at this period," states art historian Dorothy Moss.

He also had many relations with women like with his sitters Rosina Ferrara, Virginie Gautreau, and Judith Gautier.

Who did John Singer Sargent influence?

It is difficult to overstate Sargent's influence on the art world, which is seen, in the aristocratic oil portrait paintings of his friend Emil Fuchs, the contemporary British oil portrait paintings of Isabella Watling, and the earliest oil painting portraits of the American modernist painter Archibald Motley.

How many paintings did John Singer Sargent paint?

Sargent was a prolific portrait painter and artist. When he officially closed his studio in 1907, Sargent had created over two thousand (2000) watercolors, nine hundred (900) oil portrait paintings and landscape paintings, and a staggering number of works on paper by the age of fifty-one. Although his work fell out of favor with critics during the height of modernism, interest in his works has steadily increased since the 1950s and 1960s.

What style of painting is John Singer Sargent's?

Sargent's painting style is classified as impressionist and realist by critics. Sargent, on the other hand, can be considered a generalist because he mastered and combined a variety of styles, including classical oil portrait paintings, impressionism, landscapes, watercolors, and murals. Sargent believed that styles were techniques to be used rather than final representations and that knowledge of a specific style "does not make a man an artist any more than knowledge of perspective does - it is merely a refining of one's means towards representing things and one step further away from the hieroglyph."

What were John Singer Sargent's secret techniques and processes?

Not much is known of Sargent's process and technical methods of his oil painting portraits as he rarely taught. Art historian and author Stanley Olsen speculate in his book John Singer Sargent, His Portrait, published in 1986, that occasionally he used photography as an aid to his compositions. A technique that later developed into the Photorealism art movement. When Mr. John Collier was writing his book on The Art of Portrait Painting he asked John Singer Sargent for an account of his methods of creating oil portrait paintings. Sargent replied:

"As to describing my procedure, I find the greatest difficulty in making it clear to pupils, even with the palette and brushes in hand and with the model before me; to serve it up in the abstract seems to me hopeless."

Evan charter Book cover on John Singer Sargent (image credits: Archive.org)

Evan charter Book cover on John Singer Sargent (image credits: Archive.org)

A biography written in 1927 by the Honorable Evan Charteris K.C., who knew Sargent offers some insight into Sargent’s working methods, in creating his masterly oil portrait paintings as described by two of his students, Miss Heyneman and Mr. Henry Haley. The following is an extract of their experiences learning under Sargent.

Miss Heyneman’s recounting of Sargent’s Methods:

When he first undertook to criticize Miss Heyneman’s work he insisted that she should draw from models and not from friends.

“If you paint your friends, they and you are chiefly concerned about the likeness. You can’t discard a canvas when you please and begin anew – you can’t go on indefinitely until you have solved a problem.”

He disapproved (Miss Heyneman continues) of my palette and brushes. On the palette, the paints had not been put out with any system.

“You do not want dabs of color, you want plenty of paint to paint with”

Then the brushes came in for derision.

“No wonder your painting is like feathers if you use these.”

Having scraped the palette clean he put out enough paint so it seemed for a dozen pictures.

“Painting is quite hard enough without adding to your difficulties by keeping your tools in bad condition. You want good thick brushes that will hold the paint and that will resist in a sense the stroke on the canvas.”

He then with a bit of charcoal placed the head with no more than a few careful lines over which he passed a rag, so that it was a perfectly clean grayish-colored canvas (which he preferred), faintly showing where the lines had been. Then he began to paint. At the start he used sparingly a little turpentine to rub in a general tone over the background and to outline the head (the real outline where the light and shadow meet, not the place where the head meets the background), to indicate the mass of the hair and the tone of the dress. The features were not even suggested. This was a matter of a few moments. For the rest, he used his color without a medium of any kind, neither oil, turpentine, or any other mixture.

“The thicker you paint, the more color flows.”

He had put in this general outline very rapidly, hardly more than smudges, but from the moment that he began really to paint, he worked with a kind of concentrated deliberation, a slow haste so to speak, holding his brush poised in the air for an instant and then putting it just where and how he intended it to fall.

To watch the head develop from the start was like the sudden lifting of a blind in a dark room. Every stage was a revelation. For one thing, he often moved his easel next to the sitter so that when he walked back from it he saw the canvas and the original in the same light, at the same distance, and the same angle of vision. He aimed at once for the true general tone of the background, of the hair, and the transition tone between the two. He showed me how the light flowed over the surface of the cheek into the background itself.

Lady Agnew portrait painting head closeup (image credits: Wikicommons)

Lady Agnew portrait painting head closeup (image credits: Wikicommons)

If you see a thing transparent, paint it transparent; don’t get the effect by a thin stain showing the canvas through. That’s a mere trick. The more delicate the transition, the more you must study it for the exact tone.

Every brush stroke while he painted had modeled the head or further simplified it. He was careful to insist that there were many roads to Rome, and that beautiful painting would be the result of any method or no method, but he was convinced that by the method he advocated, and followed all his life, a freedom could be acquired, a technical mastery that left the mind at liberty to concentrate on a deeper or more subtle expression.

I had previously been taught to paint a head in three separate stages, each one repeating – in charcoal, in thin color-wash, and in paint – the same things. By Sargent’s method, the head is developed by one process. Until almost at the end there were no features or accents, simply a solid shape growing out of and into a background with which it was one. When at last he did put them in, each accent was studied with an intensity that kept his brush poised in mid-air until eye and hand had steadied to one purpose, and then...bling! the stroke resounded almost like a note of music. It annoyed him very much if the accents were carelessly indicated, without accurate consideration of their comparative importance. They were, in a way, the nails upon which the whole structure depended for solidity.

Order Your Oil Portrait Painting on Canvas from Photo Today

Mr. Haley’s account of his learning from Sargent:

The following extracts from Mr. Haley’s account of Sargent’s teaching at the Royal Academy Schools, 1897-1900, throw further light on his methods:

The significance of his [Sargent’s] teaching was not always immediately apparent; it had the virtue of revealing itself with riper experience. His hesitation was probably due to searching out for something to grasp in the mind of the student, that achieved, he would unfold a deep earnestness, subdued but intense. He was regarded by some students as an indifferent teacher, and by others as a “wonder”; as a “wonder” I like to regard him.

He dealt always with the fundamentals. Many were fogged as to his aim. These fundamentals had to be constantly exercised and applied.

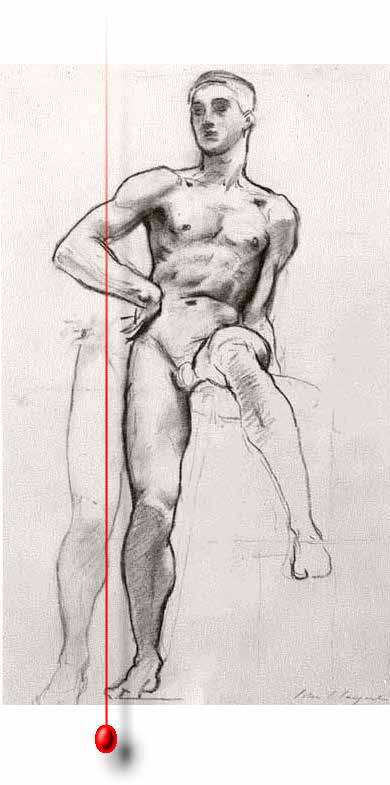

"When drawing from the model, never be without the plumb line in the left hand. Everyone has a bias, either to the right hand or the left of the vertical. The use of the plumb line rectifies this error and develops a keen appreciation of the vertical."

He then took up the charcoal, with arm extended to its full length, and head thrown well back: all the while intensely calculating, he slowly and deliberately mapped the proportions of the large masses of a head and shoulders, first the poise of the head upon the neck, its relation with the shoulders. Then rapidly indicate the mass of the hair, then spots locating the exact position of the features, at the same time noting their tone values and special character, finally adding any further accent or dark shadow which made up the head, the neck, the shoulders, and head of the sternum.

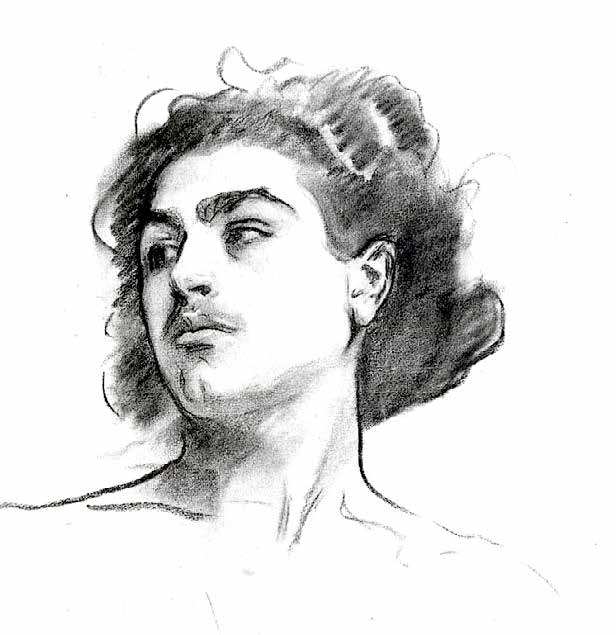

John Singer Sargent sketch of Albert de Belleroche (image credits: Wikicommons)

John Singer Sargent sketch of Albert de Belleroche (image credits: Wikicommons)

A formula of his for drawing was:

"Get your spots in their right place and your lines precisely at their relative angles."

In connection with the painting, the same principles are maintained

Painting is an interpretation of tone through the medium of color drawn with the brush. Use a large brush. Do not starve your palette. Accurately place your masses with the charcoal, then lay in the background about half an inch over the border of the adjoining tones, true as possible, then lay in the mass of hair, recovering the drawing and fusing the tones with the background, and overlapping the flesh of the forehead. The face lay in a middle flesh tone, light on the left side and dark on the shadow side, always recovering the drawing, and most carefully fusing the flesh into the background. Paint flesh into background and background into flesh, until the exact quality is obtained, both in color and tone so the whole resembles a wig maker’s block.

Madam X, head sketch (image credits: Wikicommons)

Madam X, head sketch (image credits: Wikicommons)

Then follows the most marked and characteristic accents of the features in place and tone and drawing as accurately as possible, painting deliberately into the wet ground, testing your work by repeatedly standing well back, viewing it as a whole, a very important thing. After this take up the subtler tones which express the retiring planes of the head, temples, chin, nose, and cheeks with neck, then the still more subtle drawing of mouth and eyes, fusing tone into tone all the time, until finally with deliberate touch the high lights are laid in, this occupies the first sitting and should the painting not be satisfactory, the whole is ruthlessly fogged by brushing together, the object is not to allow any parts well done, to interfere with that principle of oneness, or unity of every part; the brushing together engendered an appetite to attack the problem afresh at every sitting each attempt resulting in a more complete visualization in the mind. The process is repeated until the canvas is completed.

Sargent would press home the fact that the subtleties of paint must be controlled by continually viewing the work from a distance.

"Stand back – get well away – and you will realize the great danger there is over overstating a tone. Keep the thing as a whole in your mind. Tones so subtle as not to be detected on close acquaintance can only be adjusted by this means."

John singer sargent sketch with plumbline (image credits: wikicommons)

John singer sargent sketch with plumbline (image credits: wikicommons)

On one occasion, when the subject set for a composition was a portrait painting, the criticism was: “not one of them seriously considered.” Many we had thought quite good, as an indication of what might be tried while a portrait painting was in progress. That would not do for Sargent. A sketch must be seriously planned, tried and tried again, turned about until it satisfies every requirement, and a perfect visualization is attained. A sketch must not be merely a pattern of pleasant shapes, just pleasing to the eyes, just merely a fancy. It must be a very possible thing, a definite arrangement – everything fitting in a plan and in true relationship frankly standing upon a horizontal plane coinciding in their place with a prearranged line. As a plan is to a building, so must the sketch be to the picture.

Cultivate an ever-continuous power of observation. Wherever you are, be always ready to make slight notes of postures, groups, and incidents. Store up in the mind without ceasing a continuous stream of observations from which to make selections later. Above all things get abroad, see the sunlight, and everything that is to be seen, the power of selection will follow. Be continually making mental notes, make them again and again, test what you remember by sketches until you have got them fixed. Do not be backward at using every device and making every experiment that ingenuity can devise, in order to attain that sense of completeness which nature so beautifully provides, always bearing in mind the limitations of the materials in which you work.

The above brief extract throws light on the techniques and processes employed by Sargent to create his stunning portraitures and oil portrait paintings.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly John Singer Sargent was one of the greatest portrait painting artists of all time. Check his 20 famous works of portrait painting in Ultimate 20 Best Oil Portrait Paintings of John Singer Sargent (Ranked). His work bought alive the luxurious Edwardian era. Andy Warhol once said that Sargent's best-known oil portrait paintings captured the glamor of the time and "made everyone appear glitzy. Thinner and taller."

In the current times, the internet and social media, and sites like paintphotographs.com have made the entire process of creating an oil painting portrait easier and more convenient. A reference image can be shared to commission the portrait painting via the internet. The artist creates the oil portrait painting from photos and sends the image to the client via email and WhatsApp for approval. The painting is delivered to the client once it has been approved.

A client can commission a portrait painting artwork sitting in the United States or the Middle East, such as Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, or Oman, while the artist will execute the commission from India or Asia. It's like having an artist always nearby, whether you live in New York, California, Los Angeles, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Doha, Riyadh, or Muscat.

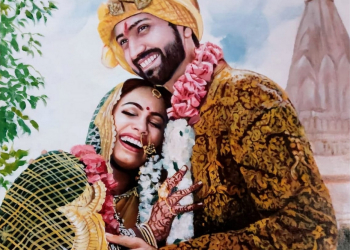

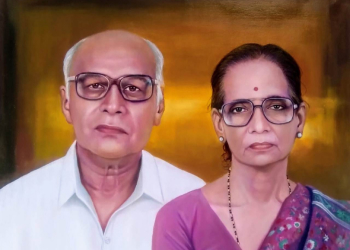

Paintings created can be Individual oil portrait paintings, couple oil portraits, children's oil portrait paintings, religious and devotional oil paintings, family painting portraits, or memorial oil portrait paintings. Artists can also create composite oil painting portraits made from two or more photos, pet portrait paintings, old masters' handmade oil reproductions, or creating new paintings from old photos, or creating handmade reproductions of contemporary art.

About Us:

Paintphotographs.com is India's leading custom art platform. We turn your favorite photos, pics, and images into luxurious handmade portrait paintings. Our work includes handmade portraits, custom oil reproductions, charcoal drawings, and sketches. As a team of accomplished artists, we use museum-quality canvas, the best international brands of colors such as Winsor & Newton and Daler Rawney. We work with various mediums, including oil, acrylic, mixed media, graphite, and charcoal.

To order a custom handmade oil portrait painting you can visit our order now page. You can order custom Wedding Paintings, Couple Paintings, Memorial Paintings, Family Paintings, Baby portraits and Children Paintings, Photo to paintings, and Pet Portrait Paintings from Photo.

You can visit our pricing page to know the prices of our portrait paintings. To connect with us ping us on our chat messenger on the website, ping us on WhatsApp, call us at 918291070650, or drop us an email at support@paintphotographs.com

You can visit our gallery pages to see our work. We make photo to paintings, couple paintings, memorial paintings, Kids and Baby Portrait paintings, God & Religious Paintings, Old Photo to Paintings, Wedding couple Paintings & Marriage Portraits, Family Paintings, Pet Portrait Paintings, Radha Krishna Paintings, Oil Portraits of Gurus, Saints & Holy Men, Charcoal and Pencil Sketches, Custom Landscape & Cityscape paintings, Contemporary Art Reproduction & Replica Paintings, Old Master Reproduction & Replica Art, Monochrome and Black & White portrait paintings, Historical Portraits and Shivaji Maharaj Paintings, Celebrity & Political Leaders Portraits. We can also merge separate photos to create a single seamless painting called Composite portraits to add deceased loved ones to make a family oil portrait as though they were present.

Our custom handmade portraits make beautiful Anniversary Gifts, Engagement Gifts, Birthday Gifts, Retirement Gifts, Housewarming Gifts, Mother's Day gifts, and luxurious gifts for many important occasions.

Paintphotographs.com provides bespoke services for art patrons, interior designers, and architects. It helps you create the perfect pieces for residential and commercial projects and serves as a platform for artists to showcase their work.

If you are an art aficionado interested in writing a guest post on art, connect with us.

Want to read more? Check our reading recommendations below! Please refer to the Notes and Reference section for sources referenced in the article.

Like this story? Then you will love our podcasts on Spotify. Listen to our deep dives and fascinating stories from the art world. Join our nearly 20,000-strong community on Facebook, WhatsApp, and X.

Want to see our art? Join our community of 500,000+ subscribers on the Paintphotographs YouTube channel, Instagram, and Pinterest for some amazing art pics & art videos!

Notes & reference section

https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/John_Singer_Sargent_His_Portrait/2pbGQgAACAAJ?hl=en

https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Strapless/0prdGAF7F3EC?hl=en&gbpv=0

https://archive.org/details/johnsargent00char/mode/2up